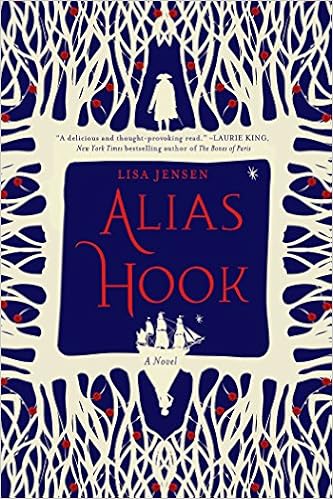

Alias Hook did something much, much worse. In Lisa Jensen's retelling of Peter Pan from the perspective of Captain Hook, she either ignorantly or willfully perpetuated some of the racial stereotypes than ran rampant in Sir Barrie's work.

Alias Hook did something much, much worse. In Lisa Jensen's retelling of Peter Pan from the perspective of Captain Hook, she either ignorantly or willfully perpetuated some of the racial stereotypes than ran rampant in Sir Barrie's work.The main thrust of the story shows how Captain Hook came to be in Neverland, and is ostensibly about him finding redemption and an escape from the murderous boy Peter through love. That part was fine - good, even, except her protagonist felt like a thinly veiled Claire Fraser. But the dire problem with this book is that Hook's path to redemption is a spiritual journey that is paved by racial otherness. The curse of being stuck in Neverland is thrust upon him by a spurned lover, who is first described as an obeah woman (which would be more Jamaican in its ancestry), but then later as a Voudo priestess (from West African states like Benin and Togo, and then transmuted into voodoo in Haiti and French America). Her treatment of Afro-Caribbean traditions as interchangeable is bad enough, but no matter which legitimate religions and cultural traditions she's co-opting, Prosperpina is always portrayed as a witch. Sorry, but witchcraft and non-Christian are absolutely not the same thing, and it felt utterly ignorant and disrespectful.

Worse still, at least for me personally given my research background in this exact phenomenon, was her portrayal of American Indians in the Neverland. Again, there was a mashup demonstrating her complete lack of cultural understanding or distinction that makes umbrella terms like "Indian" useless: teepees (Plains) and canoes (coastal) go hand in hand here, and they portrayed as are patriarchal, which is the exact opposite of many indigenous political structures. They are predictably stoic and mystical, and their simple, naturalist, romantic speech is the product of nineteenth-century white writers like James Fenimore Cooper (see The Leatherstocking Tales), who constructed a concept of Indianness for white consumption, and is just as racially unjust as blackface minstrelry. That language is replicated in this book, in the 21st century, as if there's not a damn thing wrong with it.

The most heinous and egregious choice is her description of these figures as real Indians who have fled Earth to protect their way of life. So Jensen has actually bought wholesale the nineteenth-century myth that Indians were vanished, a dying race, and that there was no place left for them on Earth. My professional historical opinion on seeing this false narrative rewritten for the sake of literature is that it endorses the atrocities endured by countless Amerindian cultures at the hands of white Christendom, and is an abomination that flies in the face of all that indigenous people have endured since first contact, and all the struggles to establish their cultural and political sovereignty in the face of powerful forces that labeled their culture as static and obsolete- an Indian was only an Indian in leather and feathers. It's a disgrace to living American Indians everywhere. That the author would be oblivious to the implications of her writing I find hard to believe in this day and age, and to willfully ignore the damage such representations have done and continue to do is utterly unacceptable.

When people of color are lumped into the same mystical categories as fairies, the perpetrators of such literary atrocities must be called out and made to answer. If the representation of racial otherness and cultural appropriation in literature matter to you at all, I urge you to abstain from purchasing this work, and any other written by Lisa Jensen.

No comments:

Post a Comment